Not everyone likes gardening, but a lot of people do—including some very busy people with big responsibilities. Because of time pressures, clients tend to ask for that immortal killer of original, complex, biodiverse design: a low-maintenance garden, which usually means a big lawn with a few classic plants scattered around the edges. Yet, if only they could access an alternate reality where time is not limited, they would love something different. Here I share a 3-step process that has given me more time for the activities that are important to me, including gardening. I hope it will inspire you to win your own battle against time or energy constraints.

Through gardens we can connect back to our ancestral landscapes and get more balance in life

When it comes to garden design, I see myself first and foremost as a wellness architect. The layout and style of the space around us can make us feel better. Or worse. A garden, however, has some notable differences from any other man-made environment because it is largely made up of plants. Our bodies and minds evolved within natural landscapes. As we spend more and more time indoors, in front of screens or in urban environments, we get severed from this experience of the natural world. Our brains become overwhelmed by an excess of artificial stimuli and intellectual tasks. Through thoughtful design, a garden can bring back opportunities for interaction with the living universe. Garden may become a tiny gate to feeling in harmony with the world.

My quest for more time and energy for the garden

At the same time, I know that for many people, this opportunity presents the challenge of how to fit gardening into their busy schedules. This has been the case for me as well. Finding a way to give my garden enough attention was both an imperative and a difficult undertaking. If I couldn’t bring myself to look after my own garden, then there was no point in designing these beautiful, verdant little private worlds if my clients couldn’t even enjoy them. In order to walk the talk, I had to make it work—really work—for me first.

You may be forgiven for thinking that, as a garden designer, I do little more than linger in gardens or do a lot of actual gardening. While I consider gardening an important part of testing ideas and connecting with my motivations for working in this profession, I am not a gardener. In the main I am no different from any other architect. Most of my time is spent researching for projects or designing (happy days), doing administration (less happy days) or dealing with sudden problems (the least happy days)—mostly indoors. Any outdoor work doesn’t mean lounging – it means surveying mess.

An experiment to turn impossible into possible

I recon that if you are reading this post, you too would like to do a bit more gardening than you are doing right now. Or do it differently. So I want to share my journey to finding more time and energy for my garden, in the hope that it will serve as an inspiring example of how to make the seemingly impossible possible. Looking back, I have realised that I can break it down into a 3-step process, in which I challenged my beliefs, shifted priorities, and started respecting my needs. It is a foundation-building thought process rather than a list of hacks. Therefore I promise no trivia along the lines of ‘block a slot in your calendar for gardening’—the sort of advice that is about as useful as a blind sniper.

Step 1 – Find out how important your garden is to you

How does your garden make you feel? What does gardening give you? Just a sore back, or also peace of mind and a sense of fulfilment? More broadly, how do you feel in nature?

Scientists have been studying the effects of nature on the human body and mind since the early 1980s. To cut a long story told in hundreds of publications, the exposure to the natural environment has been shown to soothe a stressed nervous system and improve mood, along with a variety of other physiological benefits. Individual responses, however, vary considerably, which is not surprising given how different people are.

Are you perhaps a sensitive over-thinker?

Some people tend to be very sensitive to environmental factors such as visual clutter, noise or strong light. For these individuals, such stimuli constantly demand attention and can easily overwhelm the brain’s ability to process them, leading to fatigue. Natural scenes are easier for our brains to process than built environments, not to mention the flood of information that comes with every social interaction. This makes nature an ideal setting for rest. And for those who need a bit of time alone to recharge, the garden is a perfect place for solitary contemplation; or even a temporary escape from exhausting social gatherings.

The second group of people for whom gardening can work wonders are over-thinkers. Gardening not only engages the body, but also requires full attention. It leaves little room to rehearse alternative conversations, worry about a project deadline, or consider how to resolve disagreements with the mother-in-law. Natural scenes are easy on the brain, but complex in detail, so they can be very engaging.

High sensitivity to external input and overthinking go hand in hand for me, which is not unusual for introverts. My garden creates a space where I can recharge my batteries and get some distance from all my affairs. Even 10 minutes in the garden interrupts all the clutter in my head, which is a prerequisite for both creative and rational thinking. All in all, my garden supports my psychological balance and thereby original work—it is not just a peripheral pleasure.

So let me ask you again: how important is your garden to you? Does gardening give you satisfaction? If you had unlimited time and energy, would you like to get your hands in the soil, sow, plant, nurture, watch plants grow, or harvest? These are really essential questions to sort out. Unless you decide that gardening is important—really important—there is no magic in the world that will help you find the time to do it. Maybe, all in all, you do not want to garden. Which is perfectly fine, too.

Step 2 – Identify your current limitations in finding time for your garden

If you are still here, I suppose you would like to create more space in your life for gardening. But there is something standing in the way of what you would like to do and what you are able to do. Can you say what it is?

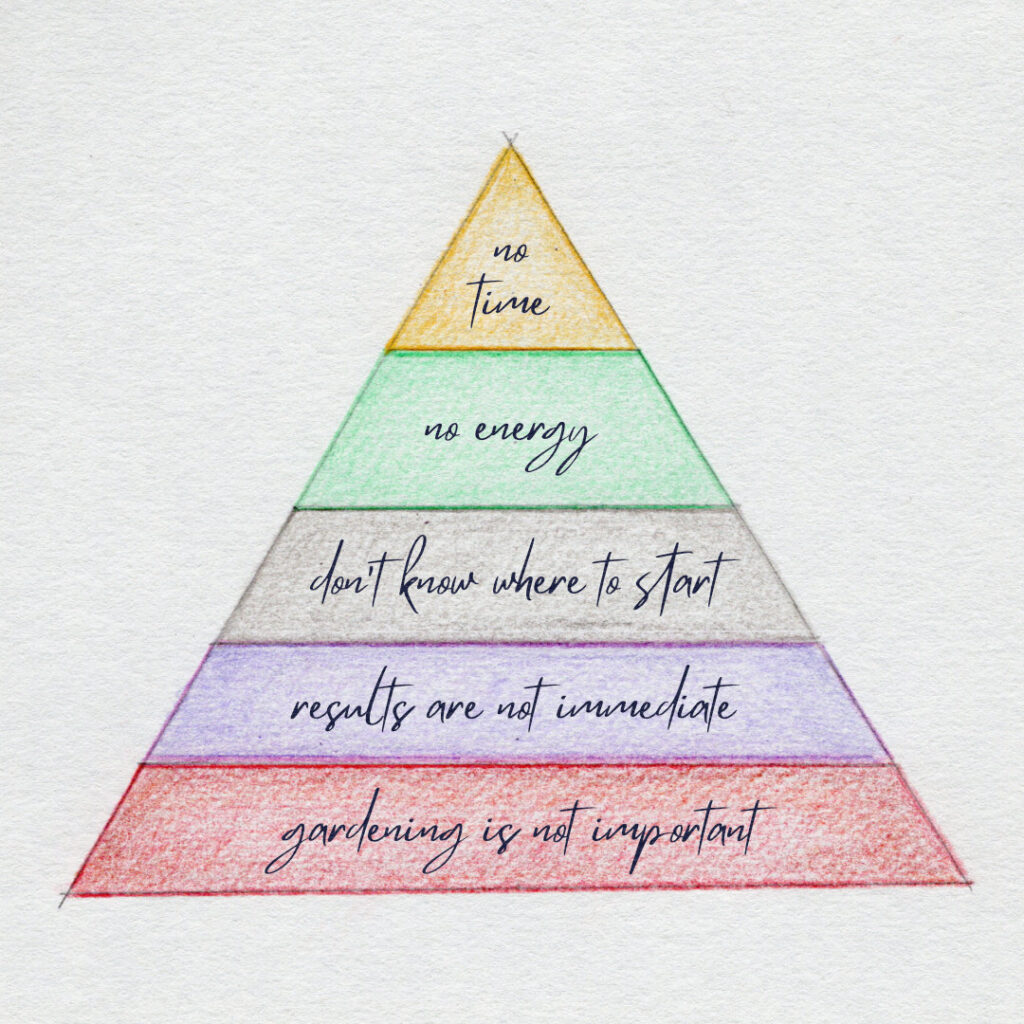

In a few decades of walking this earth, I have identified five main obstacles to my aspirations:

- Lack of time

- Lack of energy

- Lack of experience which leads to a high ‘energy of activation’

- Far-fetched outcome

- The belief that what I want to do is not important

The majority of homeowners would probably mention lack of time as the most limiting factor in taking care of their gardens. However, I think of the above list as a pyramid where the real underlying causes are hidden by the most prominent perception of ‘lack of time’.

Do you think that “gardening is just a hobby, not a serious, socially relevant activity”?

Work, family, housework, taxes and what not come first. In modern times, we’ve traded the comforts and role division of multi-generational families for freedom of choice and expression. How much do we use this freedom? From what I could observe in my own reactions and those of other people around me, cultural preconceptions about what our duties are, what is good for the society and what is selfish, hold us in an invisible grip as tight as the conservative judgement of the great-grandmother of 100 years ago. Under these circumstances, how do you rate your well-being? Is it at the top or the bottom of your list of priorities? If gardening makes you feel good, why would it end up at the bottom?

Individuals determine the wellbeing of society

I think that, paradoxically, many of us in modern western/northern societies do not place enough value on mental and physical wellbeing beyond the monetary costs of absence from work and health care. The value of simply feeling good. Perhaps because we still think that taking care of ourselves is a sin of selfishness. Yet how you feel affects everyone around you. Your good mood and relaxed demeanour strengthens the collective prosperity of the society beyond you as an individual and beyond mere economic indicators.

“How you are in the world matters”

Heidi Marke – Positive Psychologist, Zen Yoga Teacher and Gentle Rebel Coach

Still not convinced? How do you feel when someone honks aggressively after a 2 second delay when the green light comes on? Or after an encounter with a grumpy public officer? How is your day when you are standing in line with a bunch of coriander behind someone with a shopping trolley full to the brim, and they spontaneously ask you to go in front? Small acts of kindness—or unkindness—have a very big impact on other people, moving like waves of positive or negative energy through communities. Kindness rarely comes from stressed, overworked minds. I dare to suggest that doing something you enjoy is as important and valuable as submitting your taxes on time.

Preconceptions about what counts as wellness and what doesn’t can lead to unhelpful self-judgment

There are also fixed preconceived notions about what ‘taking care of oneself’ looks like. Do you consider daydreaming among greenery as an important act of self-care or as an unproductive waste of time? I used to feel guilty for those moments of doing nothing but contemplating a leaf, a flower, a bee, a ray of light. Yet if it makes sense to take a bubble bath or book a massage, why not hang out in the garden? Finally, as if these arguments weren’t enough, cultivating a plant-rich garden is a truly effective and empowering action an individual can take to combat the loss of biodiversity. It is, as hobbies go, a damn worthwhile hobby.

Does a lack of gardening experience make it difficult to get started?

The ‘energy of activation’ is a term borrowed from chemistry. It is defined as the extra amount of energy required to initiate a chemical reaction. Once the reaction is underway, it doesn’t need any additional input. In fact, some energy is recovered as products are formed. Any new activity involves uncertainty, with many small decisions to be made before it can run on autopilot. Our brains perceive uncertainty as a threat and usually prevent us from expending additional energy. Before such an activity becomes routine, the resistance is almost tangible.

Gardening has a considerable energy of activation for inexperienced practitioners. Those who have grown up in cities have been cut off from the gardening tradition of previous generations. City dwellers suddenly given a garden in later life have no idea what to do with it. It does take commitment to learn the basics. And even then, horticulture attempts to rule a network of living things under uncontrollable external circumstances. Some gardening experiments inevitably end in blind alleys. Lack of control usually makes us uncomfortable, so learning to garden also means learning to accept uncertainty. How much does fear of failing or disappointment with previous attempts stop you from gardening more? Could this be changed by shifting your attention from the outcome to the process itself? Or could you reduce your energy of activation by learning from an experienced gardener in the beginning?

The results of gardening are far in the future

With few exceptions, there is no instant garden. What I do today will usually not pay off for at least a few weeks, more often months, and not infrequently years. By contrast, simple maintenance tasks, such as mowing the lawn or tidying up the flower beds at the end of the season, have a lower activation energy because they don’t require decisions or figuring things out. They also provide an immediate visual order. When energy of activation is high and immediate gratification is low, it takes a wider horizon and a higher sense of purpose to get out to tools or a planning board. Do you have a system in place to remind you of what you want to achieve and why on a regular basis?

Where does your time go?

Procrastination. Lukewarm TV shows. News. Social media. Subscriptions to 101 services. Scrolling! Fast and easy content can easily pile up to hours (yes, hours!) a day. Even an hour a day adds up to 30 hours by the end of the month. That is more than I ever spend on gardening in a single month. Of course, there are those of you who have taken on so many responsibilities that there is nothing to leave out. Working mums with young children come to mind. If you are one of them, you still found time to read this blog, so it can’t be that bad! Besides, the gardening chores you probably do to maintain your low-maintenance garden also may take up significant amount of time.

Much time, little energy

So what is the difference between these activities and gardening? Firstly, ease. Second, a dopamine gamble—these services are designed to be addictive. Gardening requires energy, both physical and mental. Before it gives back, it takes some effort to plan what to do, or to get out there to do it. Do you often come home exhausted, even if it is not very late in the day? And when you have a free weekend, do you feel you can conquer the world, or at most move in the comfortable tracks of old habits? So which is the more limiting factor for you: time or energy?

To be honest, a lot of work in the garden takes more than 10 minutes. And booking the whole Sunday afternoon for gardening is a major challenge. For me too! To overcome the block, I’ve accepted that I don’t have to complete a job all at once. I can break it down into many small sessions according to the 3 minute rule. Once I have decided that keeping up with my garden is important, I am able to allocate the time budget to do it. Bottom line: although ‘not having enough time’ for gardening is a perfectly valid response, it may well be a symptom of a much deeper problem rather than the primary obstacle.

Step 3 – Overcoming the obstacles that prevent you from finding more time for your garden

The first step to healing is diagnosis. So the more you know about where you stand, the more likely you are to overcome the obstacles. Hopefully now your problem isn’t just a generic ‘I don’t have time to garden’.

I am not going to tell anyone how to overcome their obstacles. Now my readers might feel cheated, but in fact you would be cheated if I did. Funnily enough, I started writing this article with the intention of sharing my portfolio of productivity methods. But then I remembered that there are no one-size-fits all solutions.

Magical thinking, habits and bananas

Just because someone successful does something doesn’t mean it’s a universal key to success. For example, if we heard that a billionaire eats a banana for breakfast every day, we wouldn’t immediately start eating bananas in the belief that this would lead to outstanding financial results. However, such an absurd situation did happen to Adam Małysz, a Polish ski jumper. After a series of spectacular successes in World Cup competitions, he was confronted with empty banana plates in the athletes’ area. As soon as he revealed his eating habits, other competitors gobbled up all bananas. Sigh… One small piece of a complex training-physiological-dietary system that worked for Małysz obviously couldn’t be transferred to other jumpers with different bodies, habits and training regimes. The individual context makes all the difference.

However, if the habit makes sense in the context of productivity and success, it is much harder to notice that it is only a small part of a larger system. A facade of that system rather than a cornerstone of the foundation. Sharing such pieces out of context is misleading. That’s why I’ve decided not to offer you ‘bananas’ of my productivity hacks.

Choices I’ve made to reclaim time for my garden and other non-urgent but important activities

Nevertheless, I can tell you how I started: with a disagreement with the way things were going. With a refusal to keep putting my life on hold until the next big thing in an endless procession of urgent projects has been accomplished. With getting rid of paralysing overwhelm. And with the commitment to work with myself, not against myself. Choosing, or if necessary inventing, methods that suit my needs. Getting rid of those that make me feel miserable. I can only testify that I have spent a great deal of energy over many years trying to fit myself into frameworks that were unsuitable for my psychological make-up. Like, for example, strict time management. They worked for other people, but not for me. Frankly, bananas give me indigestion.

I found someone who showed me how to get where I wanted to be

Then I realised: If banana breakfasts aren’t for me, I’d better get someone on board to teach me how to cook. There are no shortcuts, no magic wand that can conjure up an abundance of time from one day to the next. It is a deep process. Guidance, though, makes this process easier, faster and more efficient. And a lot more fun. One thing I learnt from my coach was not to argue for my limitations. To paraphrase Tom Ford, whether I believe I have time or not, I am right.

In sight, in mind, in action

There will always be more exciting opportunities and projects than any one person can handle. Life happens and it is so easy to get knocked off course. Therefore, to stay committed to my goals, I have also embedded practices to keep my purpose and aspirations in life at the centre of my attention. They serve as a reference point for everything I do. Is cultivating a beautiful garden on your dream board? Then make sure you remember about it.

If you want to know more about how I started to take back control of my life, you can find out a lot more in this interview. No banana analogies, I promise!

Inasmuch as I am sceptical about the usefulness of feeding anyone bananas, if you’re still interested in my productivity and prioritisation methods, send me an email or leave a comment on social media. I might consider a follow-up post.